The United States, wading into the international efforts to shape Greece’s economic and geopolitical orientation, is pushing the leftist government in Athens to resist Russia’s energy overtures.

A State Department envoy in Athens urged Greece on Friday to embrace a Western-backed project that would link Europe to natural gas supplies in Azerbaijan, rather than agree to a gas pipeline project pushed by Moscow.

A State Department envoy in Athens urged Greece on Friday to embrace a Western-backed project that would link Europe to natural gas supplies in Azerbaijan, rather than agree to a gas pipeline project pushed by Moscow.

The dueling sales pitches, reminiscent of a Cold War struggle, come as debt-burdened Greece is desperate for new sources of revenue of the sort that a gas pipeline could bring.

In an interview in Athens on Friday, before meeting with Greek officials, the State Department envoy, Amos J. Hochstein, said Greece would increase its appeal to Western investors — and would help reduce the European Union’s dependence on Russian gas supplies — if it declined to play host to a pipeline proposed by the Russian state-controlled energy giant Gazprom.

That pipeline would carry Russian gas to Europe through Turkey and Greece, bypassing pipelines that run through Ukraine.

Washington’s push against the Russian pipeline project follows a stalemate in negotiations between Greece and its international creditors aimed at unlocking further loans. Even as Greece’s European neighbors are focused on the country’s ability to repay its debts, the United States is intent on addressing Greece’s geopolitical value as a NATO outpost at the southern tip of the Balkans and as an important gateway for energy from Central Asia.

Mr. Hochstein said Moscow’s interests were not aligned with Greece’s financial needs. The Russian pipeline plan, he said in the interview, “is not an economic project” but is “only about politics.”

The geopolitical tug of war over Europe’s energy supply is growing increasingly intense.

The Russian president, Vladimir V. Putin, spoke by telephone with Prime MinisterAlexis Tsipras of Greece about the Gazprom pipeline project on Thursday. And Mr. Tsipras’s office has confirmed his country’s readiness to take part in the construction of a Greek pipeline to transfer Russian natural gas from the Greek-Turkish border to Europe.

The Greek foreign minister, Nikos Kotzias, has said that the Greek portion of the Russian-backed project could be worth billions of dollars to his country. Turkey and Russia, however, have still not agreed on the Turkish part of that proposed pipeline, which means any Gazprom deal with Greece would be meaningless unless the Turks and the Russians can come to terms.

In a speech in Berlin in April, Gazprom’s chairman, Alexey Miller, described Turkish Stream as “a real blessing for the entire European gas market,” and he said the project would follow European rules. According to a transcript posted on Gazprom’s website on Friday, Mr. Miller told Russian state media that “Turkish Stream will start in December 2016.” Mr. Miller also said the company had “made a decision to start building the maritime section of Turkish Stream,” according to the transcript.

Turkish officials on Friday indicated that discussions with Gazprom were headed in a positive direction. But those officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity in keeping with government protocol, said any final agreement would only be reached after further negotiations.

The discussions between Moscow and Athens come as Greece’s funds are running low and it desperately seeks new investment. Without new revenue or additional loans, Greece risks defaulting on billions of dollars of foreign debt in coming months. That could force a Greek exit from the euro currency union and would have unpredictable implications for financial markets in Europe and beyond.

Athens is expected to be able to pay an installment of about 750 million euros, or about $850 million, that is due on Tuesday to the International Monetary Fund. But when eurozone finance ministers meet on Monday in Brussels, there will be urgent questions about how long Greece can manage without fresh funds.

European and international lenders continue to hold back on releasing €7.2 billion in funds from a bailout program, demanding economic overhauls in Greece that the Tsipras government has so far been reluctant to carry out.

Although the Greek news media reported on Friday that Greece and its creditors were edging closer in their negotiations, with a series of tax increases under consideration, the contentious issues of pension and labor overhauls continued to hamper progress. Mr. Tsipras said in Parliament on Friday that he was optimistic that there would be a “happy end” to the talks soon. But he also emphasized that Greece was sticking to its “red lines” of protecting pensions and workers’ rights.

While revenue from a new gas pipeline could be years away, such a project — whether with Russian or Western backing — would have obvious allure for Greece.

The Russian proposal is for a pipeline called Turkish Stream. It is intended to replace an earlier Russian initiative for a pipeline to Europe called South Stream, which Mr. Putin was forced to abandon late last year because of European Union rules that would have made the project unpalatable to Moscow by requiring Gazprom to share the pipeline with other suppliers. The South Stream pipeline, running under the Black Sea, would have brought gas into the European Union through Bulgaria.

Mr. Hochstein, the American official, said on Friday that the pipeline he was promoting — called the Southern Gas Corridor project — was farther along in construction. It would involve multiple companies, including the British energy giant BP, and countries including Georgia and Turkey, and it would bring together a series of pipeline projects stretching from Azerbaijan to Italy, through Greece.

When the route now known as the Southern Gas Corridor was first proposed more than a decade ago, it was called Nabucco and did not include Greece. Instead, its entry point to the European Union would have been Bulgaria. But Azerbaijan subsequently selected other routes for transporting its gas, including one that would run from the Turkish border through Greece and Albania into Italy. Work has begun in eastern Turkey on another portion of the pipeline.

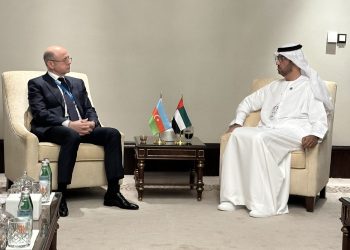

Greece’s government, and its predecessor, have both agreed in principle to the Greek portion of the pipeline from Azerbaijan. But Athens and the Azerbaijanis have not yet been able to come to terms on the financial portion of a deal and other details. Mr. Hochstein on Friday was urging Greece to press ahead with the project.

“It is an excellent project for Greece as it will create a significant amount of jobs,” Mr. Hochstein said.

In a statement released on Friday, the United States Embassy in Athens said the portion of the pipeline crossing Greece would result in €1.5 billion in foreign investment in Greece, generate 10,000 jobs during construction, and provide many millions of euros in revenue each year for the next quarter-century.

Mr. Hochstein met with the Greek energy minister, Panagiotis Lafazanis, who said afterward that there had been a “very essential and honest exchange of views.”

“We want a multilevel and independent energy policy that will be formed exclusively on the basis of our national interest, the interest of the Greek people and, of course, the cooperation and energy security in our region and in Europe,” Mr. Lafazanis said.

Greece’s commitment to the Southern Gas Corridor project could help it attract further investment to develop its offshore gas resources, Mr. Hochstein said, at a time when other Mediterranean nations like Israel and Cyprus have made significant discoveries of natural gas.

The European Commission in Brussels, the executive arm of the European Union, has long accused Moscow of using gas pipelines, including ones not yet built, to exercise control over European energy systems and to partition supplies and keep prices high — especially in Baltic countries like Lithuania with few alternatives for suppliers.

Last month, after years of European Union threats of taking such an action, Margrethe Vestager, the European antitrust chief, charged Gazprom with abusing its dominance in natural gas markets — a move amounting to a direct challenge to the authorities in Moscow.

Ms. Vestager, in making those formal charges, also said that Gazprom might have been leveraging its powerful market position in Bulgaria and Poland by making supplies of gas conditional on those countries’ agreeing to take part in pipeline projects like South Stream to carry Russian gas into Europe.

Gazprom could eventually face a fine exceeding €10 billion. But the larger worry for Gazprom in that case is the prospect of being forced to allow more competition in markets it has long controlled.

Mr. Hochstein said on Friday that Gazprom’s proposed Turkish Stream would be bad for Europe because it would extend Europe’s dependence on Russian gas. Running a Southern Corridor pipeline through Greece would benefit Europe and would enhance Greece’s longer-term goals of diversification and of developing its own energy resources, he said.