The leaders of all five littoral states attended the fourth Caspian Sea summit in the Russian city of Astrakhan yesterday. The latest meeting was more significant than previous summits held in Turkmenistan in 2002, Iran in 2007 and Azerbaijan in 2010, as the parties reached important agreements on some issues. Yet, others continue to divide them, with implications that reach far beyond the Caspian.

At yesterday’s summit, the five littoral state presidents—Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Turkmenistan’s Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov, Azerbaijan’s Ilham Aliyev, Iran’s Hassan Rouhani and Kazakhstan’s Nursultan Nazarbayev—renewed their commitment to keeping non-Caspian countries from establishing a military presence on the sea. Regarding their own armed forces, the sides agreed to ensure “a stable balance of arms in the Caspian Sea,” while calling for limiting military construction to “reasonable sufficiency, taking into account the interests of all parties without harming the security of each other.”

They also reached a new agreement on two types of maritime zones on the sea, one granting sovereignty over the area out to 15 nautical miles beyond littoral states’ shores, and another delimiting exclusive fishing rights up to 25 nautical miles from their coasts. Their discussions also covered taxation, customs, joint rescue missions and other issues. Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev proposed that the parties consider establishing a free trade zone and eventually an international organization, which would go beyond these periodic leadership meetings. Perhaps most importantly, they agreed in principle that the five littoral states would jointly develop the waters that extend beyond their fishing zones. Putin said he was hopeful that the littoral states could negotiate a convention resolving the legal status of the Caspian Sea before they met at their next summit in Kazakhstan at a date to be determined.

The five littoral states have long differed on how to divide the seabed and waters of the world’s largest inland sea. Iran, being the country with the shortest coastline, has argued that each state should have sovereignty over an equal area of the Caspian’s sea floor and surface, and that major constructions on the seabed, namely underwater energy pipelines, should require the consent of all littoral states. While Moscow favors the latter proposal, which would protect its overland pipelines connecting Central Asian energy supplies to Europe, it has advocated for dividing the seabed according to the median line while leaving the adjacent waters open to common navigation by the littoral states. According to this method, supported by Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan and opposed by Iran, Kazakhstan would receive 28.4 percent of any coastal sovereignty zones, Azerbaijan 21 percent, Russia 19 percent, Turkmenistan 18 percent and Iran 13.6 percent.

The different positions are driven by competing interests, particularly regarding energy supplies and routes. Iran has disputes with Azerbaijan over possession of some offshore fields, while Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan are eager to develop undersea pipelines to diversify their oil and gas export routes to Europe.

Thus far, the littoral countries have striven to manage their mutual tensions through diplomacy and other non-military means. But in addition to using diplomatic and commercial tools, the five littoral countries have been strengthening their naval presence in the Caspian Sea. In the process, they have transformed what had been primarily local coast guards into naval forces that could defend offshore oil and gas infrastructure, uphold their national fishing and other commercial rights, and ensure that their national interests are not ignored by the other parties. The governments of the Caspian littoral states have justified their respective naval buildups by the need to combat terrorists, but the fleets they are developing could be used to fight other navies as necessary.

Following the disintegration of the Soviet Union and its armed forces in 1991, Russia inherited the largest share of former Soviet military assets, including in the Caspian. Until recently, the Russian Ministry of Defense has provided inadequate funding to sustain its Caspian Flotilla. But in recent years this fleet, like the rest of the Russian military, has received hefty resource boosts, including the acquisition of more-modern and effective warships. Iran has the second-strongest navy in the Caspian and has employed it in the past to enforce Tehran’s claims over Caspian resources. In July 2001, for instance, Iranian warships and aircraft skirmished with two Azerbaijani research vessels exploring the Araz-Sharg-Alov/Alborz oil region in the southern Caspian. In September 2012, the Iranian navy practiced laying mines and other military missions in the Caspian Sea. The Iranian government has also been augmenting its Caspian naval power. In 2013, the Iranian Ministry of Defense completed construction of a 2,000-ton dry dock in the Caspian. Last year, the Iranian Navy also deployed its indigenously produced Jamaran-2 destroyer to the Caspian. This 1,420-ton Mowj-class warship can carry helicopters, torpedoes and artillery systems, and launch various surface-to-surface and surface-to-air missiles, as well as advanced artillery and torpedo systems.

Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan have also been buying some modern warships, but Azerbaijan has the largest naval expansion program of the remaining littoral states. Thanks to the country’s surging oil and gas revenues, the Azerbaijani armed forces have been implementing a sustained military modernization effort, including a major arms deal with Israel. Most of this buildup is directed against Armenia, but Azerbaijan has also been buying coastal craft from Israel.

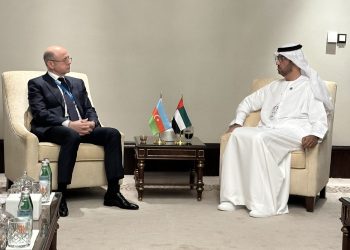

Meanwhile, the more severe international sanctions on Iran appear to have softened Tehran’s approach to its Caspian neighbors, which are not bound by Western sanctions policies. On Aug. 1, the European Union’s latest sanctions limiting involvement of citizens of European Union member states with the Iranian oil industry came into effect. Later that month, Iran’s Khazar Exploration and Production Company (KEPCO) signed a memorandum of understanding on joint exploration and production of oil in the Caspian with the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) during a visit to Iran by a SOCAR delegation. At yesterday’s summit in Astrakhan, Rouhani held a private meeting with Aliyev and told the Azerbaijani president that he wanted to see more cooperation in the fields of commerce, environment, energy and tourism. Yet, in an apparent allusion to Israel and the West, he cautioned that, “The security and development of both countries are interrelated and we should not allow the states that are against the promotion of friendly relations between the two countries to hamper these ties.”

Though the Caspian Sea summit has attracted little attention, the issues at stake carry implications for a range of interlinking challenges currently in the spotlight, from Russia’s influence in its near abroad to Iran’s efforts to reduce its international isolation and Europe’s energy security. The Caspian is a hub linking several crucial geopolitical regions, and how the current issues dividing its littoral states are resolved will have an impact felt far beyond its shores.

Richard Weitz is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute and a World Politics Review senior editor. His weekly WPR column, Global Insights, appears every Tuesday.