But the authoritarian president pins his hopes on a “Turkmen Las Vegas”

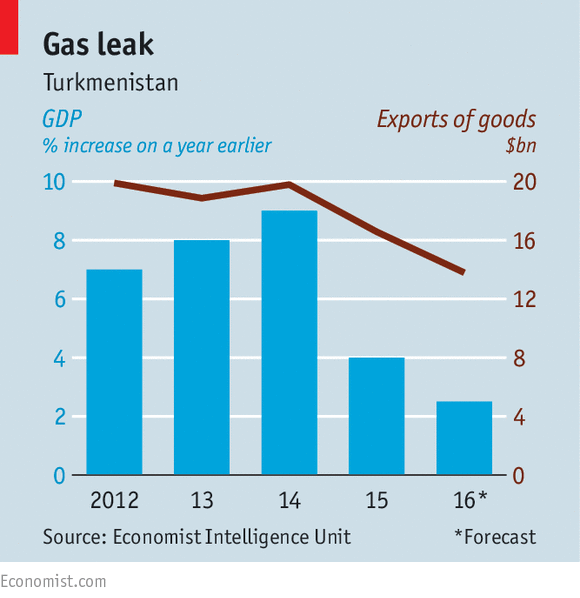

The price of natural gas has since halved, however, with dire consequences. Gas accounted for a quarter of GDP and half of all government revenue. The low price means the economy has slowed markedly (see chart), and the budget has swung from a surplus of nearly 10% of GDP in 2012 to a projected deficit of 3% this year. Dwindling foreign-exchange reserves equate to just nine months of imports.

For ordinary people, life is getting tougher. The government has raised the prices of subsidised electricity, gas and water. The devaluation of the manat, the currency, has pushed up already-high inflation: food prices rose by 28% in 2015. There are shortages of basic goods, such as flour, in some provinces. Bosses at state-owned firms, which dominate the economy, have ordered mass lay-offs. Even farming is state-controlled. Foreign analysts estimate that as many as 60% of workers are in effect unemployed. For many of those who do still have jobs, wages are said to be months in arrears.

Recent sackings of high-level government officials suggest that the president is trying to deflect growing public frustration over the deteriorating state of the economy. He also continues to foster a cult of personality: he has added books he claims to have written to the national curriculum, for example, and erected a gold statue of himself in the middle of the capital, Ashgabat, after dismantling one put up by his predecessor. Although widespread unrest is unlikely—Turkmenistan is a police state—Mr Berdymukhammedov doubtless wants to restore at least a semblance of economic stability before the next stage-managed election in February. (In the most recent election, in 2012, he ran against six other candidates, but still managed to attract 97% of the vote.)

Stabilising the economy will be difficult. Russia, which once imported 40bn cubic metres of Turkmenistani gas a year, called off all purchases in January. The lifting of Western economic sanctions against Iran, another important buyer of the country’s gas, might allow it to develop more of its own vast gasfields, and thus import less. Unhelpful or unstable neighbours block most export routes (see map), leaving China as the only other customer for Turkmenistan’s gas. But it is uncertain how much cash it earns from those sales: much of the gas it sends to China serves as payment in kind for billions of dollars in loans it has received since 2009.

Mr Berdymukhammedov’s answer is to develop a different industry: tourism. In September a new, falcon-shaped airport opened in Ashgabat. It reportedly cost $2.4bn to build and is the largest in Central Asia, with a capacity of 17m passengers a year. The government is also spending $5bn on a marble-clad sports complex that will host the Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games next year. The Avaza region in the west is being transformed into a “Turkmen Las Vegas”, replete with big casino resorts, according to the foreign ministry.

The Central Asian despotate makes an unlikely tourist magnet. It has one of the most restrictive visa policies in the world. Those who manage to obtain a tourist visa must still hire a guide, who doubles as a government minder. There is not much in the way of spectacular ruins, pristine beaches or pulsing nightlife. There is no shortage of spectacular white elephants, however.

http://www.economist.com/